If you work with web data, you have probably heard someone mention "the LinkedIn case" when discussing whether scraping is legal. The hiQ Labs v. LinkedIn lawsuit became the most cited legal precedent for web scraping in the United States, shaping how courts, companies, and practitioners think about automated data collection.

But the case is more nuanced than the headlines suggested. It was not a simple victory for scrapers. Over five years of litigation, through district courts, the Ninth Circuit, the Supreme Court, and back again, the case produced important rulings about the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act (CFAA), only to end in a settlement that saw hiQ paying damages and agreeing to destroy all scraped data.

Understanding what actually happened, and what it means for your scraping projects, requires going deeper than "scraping public data is legal." This guide walks through the full case history, explains the key legal concepts, and outlines what the ruling means for web scrapers in 2026 and beyond.

The Background: What Started the Dispute

The conflict began in May 2017, when LinkedIn sent hiQ Labs a cease - and - desist letter demanding that the company stop scraping LinkedIn's publicly available member profiles.

Who Was hiQ Labs ?

hiQ Labs was a San Francisco - based data analytics company.They specialized in workforce analytics, helping employers understand hiring trends, predict employee turnover, and identify skill gaps.Their business model relied on analyzing data from publicly visible LinkedIn profiles, information that any visitor could see without logging in.

hiQ's products included "Keeper," which predicted which employees were likely to leave a company, and "Skill Mapper," which analyzed workforce capabilities. Both products depended on scraping publicly accessible LinkedIn profile data at scale.

LinkedIn's Position

LinkedIn argued that hiQ's automated scraping:

- Violated LinkedIn's User Agreement, which prohibited automated data collection

- Harmed LinkedIn members' privacy expectations

- Interfered with LinkedIn's own data products (LinkedIn sells premium access to talent data)

- Could be prosecuted under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act as unauthorized access

- Interfered with LinkedIn's own data products (LinkedIn sells premium access to talent data)

- Harmed LinkedIn members' privacy expectations

The cease - and - desist letter threatened legal action under the CFAA, California Penal Code, and various state laws if hiQ continued scraping.

hiQ's Response

Rather than comply, hiQ filed a preemptive lawsuit seeking a declaratory judgment that its scraping activities were legal.hiQ argued that publicly accessible data, available to anyone with a web browser, could not be "unauthorized" under the CFAA.They also sought a preliminary injunction preventing LinkedIn from blocking their access.

This set the stage for one of the most important legal battles in web scraping history.

The Case Timeline: Five Years of Litigation

The case wound through the court system from 2017 to 2022, producing multiple significant rulings.

2017: District Court Grants Preliminary Injunction

In August 2017, Judge Edward Chen of the U.S.District Court for the Northern District of California granted hiQ's preliminary injunction. The court ordered LinkedIn to remove technical barriers blocking hiQ's access and prohibited LinkedIn from taking legal action against hiQ under the CFAA.

The district court's reasoning focused on the "public" nature of the data. Since any internet user could view LinkedIn profiles without logging in, hiQ's access was not "unauthorized" in any meaningful sense.

This was an early victory for hiQ, but it was only the beginning.

2019: Ninth Circuit Affirms the Injunction

LinkedIn appealed, and in September 2019, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals upheld the preliminary injunction in a decision that became widely cited by scraping advocates.

The three - judge panel concluded that hiQ was likely to succeed on its claim that scraping publicly accessible data does not violate the CFAA.The court characterized the CFAA as an "anti-intrusion statute" designed to prevent hackers from breaking into protected systems, not a law meant to prevent access to information anyone can view.

Key language from the ruling:

"The CFAA is best understood as an anti-intrusion statute and not as a 'misappropriation statute'... When a computer network generally permits public access to its data, a user's accessing that publicly available data will not constitute access without authorization under the CFAA."

The Ninth Circuit emphasized the distinction between bypassing security measures(which could violate the CFAA) and accessing data that is freely available(which likely does not).

2020: LinkedIn Petitions the Supreme Court

LinkedIn sought Supreme Court review, arguing that the Ninth Circuit's interpretation conflicted with rulings from other circuits and created legal uncertainty for website operators.

2021: Supreme Court Vacates and Remands

In June 2021, the Supreme Court took an unusual step.Rather than granting full review, the Court vacated the Ninth Circuit's judgment and sent the case back for reconsideration in light of its recent ruling in Van Buren v. United States.

Van Buren v.United States: The Case That Changed Everything

To understand what happened next, you need to understand Van Buren.

The Van Buren Facts

Nathan Van Buren was a Georgia police sergeant who had legitimate access to a law enforcement database.He was caught using that access to look up license plate information in exchange for money from a private individual.The question was whether accessing a database for an improper purpose, when you otherwise have authorized access, constitutes "exceeding authorized access" under the CFAA.

The Supreme Court's Narrow Interpretation

In a 6 - 3 decision authored by Justice Amy Coney Barrett, the Supreme Court held that "exceeds authorized access" under the CFAA covers only those who access specific files, folders, or databases that are entirely off - limits to them.It does not cover those who have authorized access but use that access for improper purposes.

In plain terms: if you have permission to be in the room, using the information for a bad reason does not make your access unauthorized.The CFAA is about the gate, not the motive.

This ruling narrowed the CFAA significantly.It suggested that violating a website's terms of service, while potentially a breach of contract, would not automatically be a federal crime under the CFAA.

Why Van Buren Mattered for hiQ

The Supreme Court vacated the hiQ ruling because Van Buren changed the interpretive framework for understanding "authorization" under the CFAA.The Ninth Circuit needed to reconsider whether its analysis held up under this new, narrower interpretation.

2022: The Ninth Circuit Doubles Down

In April 2022, the Ninth Circuit reconsidered the case in light of Van Buren and reached the same conclusion, but with even stronger reasoning.

The court found that Van Buren actually reinforced its original position.If "exceeds authorized access" applies only when someone accesses areas that are completely off - limits, then accessing publicly available data cannot trigger CFAA liability.There is no "gate" to pass through when the data is open to everyone.

The court wrote:

"Van Buren reinforces our conclusion that the concept of 'without authorization' does not apply to public websites."

This April 2022 ruling was the high - water mark for hiQ's legal position. The Ninth Circuit had now twice affirmed that scraping publicly accessible data likely does not violate the CFAA.

The Unexpected Ending: Settlement and Damages

Just when it seemed hiQ had won, the case took a dramatic turn.

November 2022: District Court Rules on Breach of Contract

While the CFAA questions bounced between appellate courts, the underlying case continued in district court.In November 2022, Judge Chen ruled on motions for summary judgment regarding LinkedIn's breach of contract claims.

The court found that hiQ had breached LinkedIn's User Agreement through its automated scraping activities. Crucially, the court also found that hiQ had used fake accounts and hired contractors ("turkers") to create fake profiles that bypassed LinkedIn's login requirements to access data not available publicly.

This was a critical distinction.The earlier CFAA rulings addressed publicly visible data.But hiQ had also scraped data that required login access, using deceptive practices to obtain it.

December 2022: Private Settlement

Facing potential liability on multiple claims, the parties reached a private settlement.The terms were stark:

- ** Permanent injunction **: hiQ agreed to stop all scraping of LinkedIn data

- ** Data destruction **: hiQ was required to delete all scraped data, source code, and algorithms derived from LinkedIn data

- ** Financial damages **: LinkedIn was awarded $500,000 in damages

- ** Liability concessions **: hiQ stipulated that LinkedIn could establish liability under the CFAA for accessing password - protected pages with fake accounts, California state computer access laws, common law trespass to chattels, and misappropriation

- ** Financial damages **: LinkedIn was awarded $500,000 in damages

- ** Data destruction **: hiQ was required to delete all scraped data, source code, and algorithms derived from LinkedIn data

The settlement was "conclusive" in favor of LinkedIn, according to court filings.

What Happened to hiQ ?

By the time of the settlement, hiQ Labs was essentially dormant.The prolonged litigation had consumed the company.While hiQ won important legal battles regarding the CFAA and public data, the company itself did not survive.

What the Case Actually Decided

The hiQ v.LinkedIn case produced binding legal precedent in some areas and non - precedential outcomes in others.Here is what we know.

The Ninth Circuit Precedent(Still Valid)

The Ninth Circuit's rulings remain controlling law in the Ninth Circuit (California, Oregon, Washington, Arizona, Nevada, Idaho, Montana, Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and Northern Mariana Islands). These rulings established:

- ** Accessing publicly available data likely does not violate the CFAA ** because there is no "authorization" barrier to bypass

- ** The CFAA is an anti - intrusion statute **, not a general restriction on data use

- ** Website operators cannot unilaterally create CFAA liability ** by sending cease - and - desist letters for accessing public data

These principles influence courts nationwide, though they are not binding outside the Ninth Circuit.

What the Settlement Did NOT Establish

The settlement is a private agreement between parties.It does not create legal precedent.Specifically:

- The stipulated CFAA liability for accessing password - protected pages is not a court ruling that would bind other cases

- The breach of contract finding was fact - specific to hiQ's practices

- Other companies scraping public data are not affected by hiQ's concessions

- The breach of contract finding was fact - specific to hiQ's practices

The Remaining Legal Risks

The case clarified CFAA exposure but left other risks intact:

- ** Breach of contract **: Violating Terms of Service can lead to civil liability

- ** Trespass to chattels **: If scraping damages or interferes with systems, liability may apply

- ** State computer access laws **: Some states have broader unauthorized access statutes

- ** Copyright infringement **: Copying protected content remains actionable

- ** Data protection laws **: GDPR, CCPA, and other regulations independently govern personal data collection

- ** Copyright infringement **: Copying protected content remains actionable

- ** State computer access laws **: Some states have broader unauthorized access statutes

- ** Trespass to chattels **: If scraping damages or interferes with systems, liability may apply

Practical Implications for Web Scrapers

So what does this all mean for your scraping projects ? Here is the practical takeaway.

What Is Relatively Safe

Based on hiQ and subsequent cases, scraping publicly available data in the United States is unlikely to violate the CFAA when you:

- Access only data visible to unauthenticated users

- Do not bypass CAPTCHAs, login walls, or other access controls

- Do not use fake accounts or credentials

- Respect reasonable rate limits to avoid system damage

- Do not republish copyrighted content

- Respect reasonable rate limits to avoid system damage

- Do not use fake accounts or credentials

- Do not bypass CAPTCHAs, login walls, or other access controls

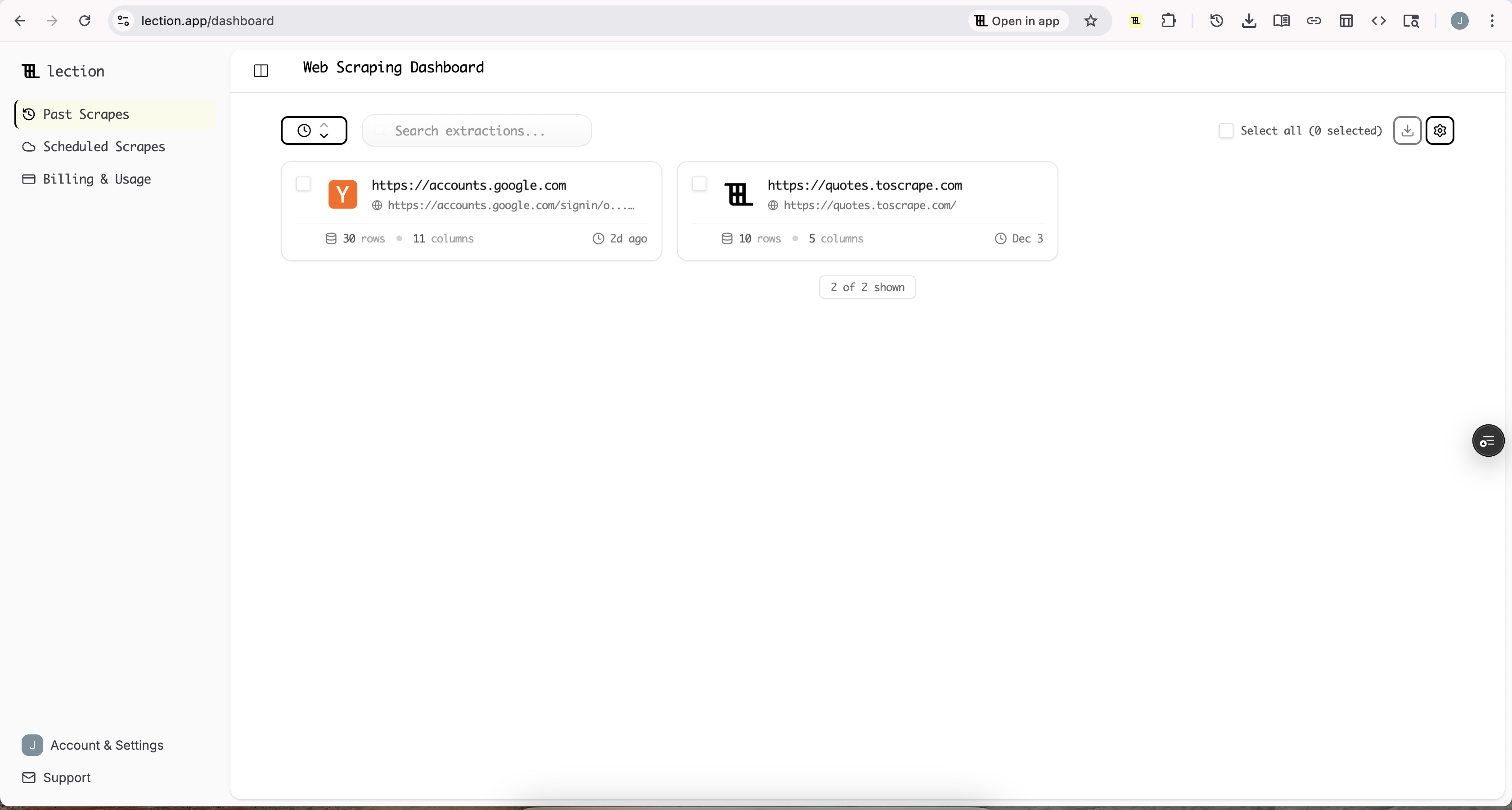

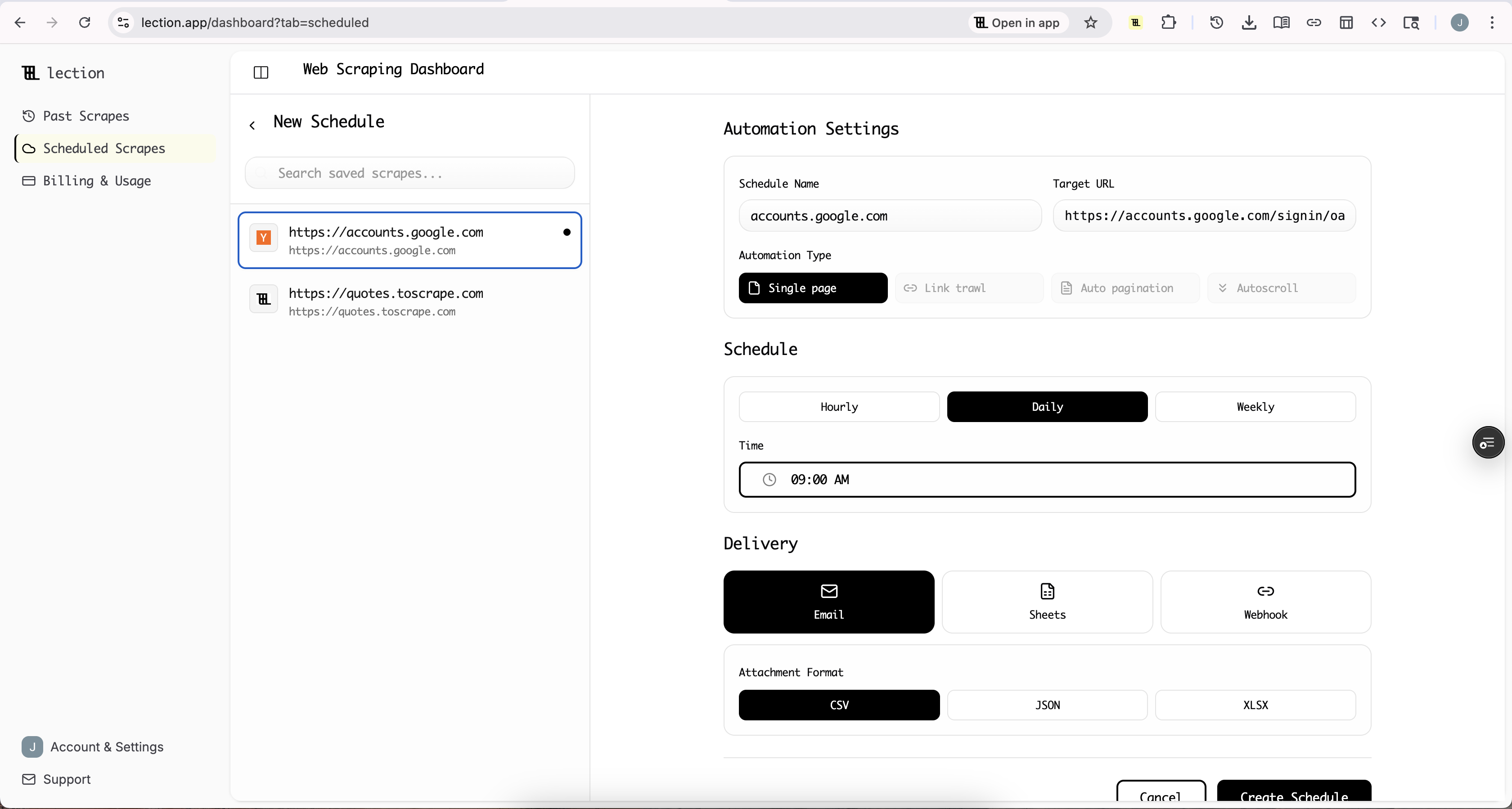

Tools likeLection that operate within your browser, extracting data you can already see, align with these principles.You are not bypassing any authorization gates; you are automating what you could do manually.

What Remains Risky

Even after hiQ, these practices create legal exposure:

- Bypassing access controls: If a website requires login, scraping that content with fake credentials creates CFAA risk

- Violating Terms of Service: While likely not criminal, ToS violations can lead to breach of contract claims

- Collecting personal data: Privacy regulations like GDPR apply regardless of CFAA status

- Copying protected content: Scraping for republication of copyrighted material invites litigation

- Damaging systems: Overwhelming servers with requests can constitute trespass to chattels

- Copying protected content: Scraping for republication of copyrighted material invites litigation

- Collecting personal data: Privacy regulations like GDPR apply regardless of CFAA status

- Violating Terms of Service: While likely not criminal, ToS violations can lead to breach of contract claims

The Terms of Service Question

One key lesson from hiQ: even when the CFAA does not apply, breach of contract claims can still succeed.

LinkedIn's Terms of Service prohibited automated scraping. hiQ violated those terms. While those violations did not constitute federal crimes under the CFAA, they did provide grounds for civil liability.

Website operators cannot criminalize public access through their terms, but they can potentially pursue damages if you agree to terms and then violate them.

The safest approach is to review a site's terms before scraping and, if terms prohibit scraping, to evaluate whether your use case falls within potential exceptions or whether the legal risk is acceptable.

The Broader Legal Landscape in 2025

hiQ did not resolve all questions about web scraping legality.The legal landscape continues to evolve.

Meta v.Bright Data(2024)

In January 2024, a federal judge ruled against Meta in its lawsuit against data scraping company Bright Data.The court found that Bright Data could only violate Meta's terms of service if Meta proved that Bright Data scraped data while logged into a Meta account. When Meta could not prove this, the case collapsed.

This ruling reinforced the public data principle: if data is visible without authentication, accessing it is harder to attack under existing legal theories.

Clearview AI Settlements(2025)

Facial recognition company Clearview AI faced multiple lawsuits for scraping billions of images from social media platforms.In 2025, Clearview settled a class action lawsuit, agreeing to pay approximately $51 million and award plaintiffs 23 % of company equity.

The Clearview cases focused primarily on biometric privacy laws rather than the CFAA, showing how different legal frameworks apply to different types of data.

AI Training and Scraped Data

The rise of large language models has intensified scrutiny of web scraping for AI training.Authors, artists, and publications have filed lawsuits challenging the use of their content to train AI systems.

These cases raise copyright questions distinct from the CFAA issues in hiQ.The outcome of ongoing litigation will shape whether and how scraped data can be used for machine learning.

How to Scrape Responsibly Today

Given the legal landscape post - hiQ, here are practical guidelines for responsible data extraction.

Do Your Legal Homework

Before scraping any site:

- Review the site's Terms of Service

- Check for robots.txt directives([learn how to read robots.txt](/blogs/complete - guide - to - robots - txt -for-web - scrapers))

- Determine if the data is truly public or behind access controls

- Assess whether personal data is involved and what privacy laws apply

- Consult legal counsel for high - stakes commercial scraping

Respect Technical Boundaries

Technical choices signal legal intent:

- Access only data visible without login

- Do not bypass CAPTCHAs or access controls

- Use reasonable request rates

- Identify your scraper in User - Agent strings

- Honor robots.txt when ethically appropriate

- Identify your scraper in User - Agent strings

- Use reasonable request rates

- Do not bypass CAPTCHAs or access controls

Choose Tools That Align with Legal Principles

Browser - based scrapers likeLection that work within your browser session, extracting data you can already see, align naturally with the legal framework established in hiQ.You are not hacking, bypassing, or intruding.You are automating observation of public information.

Document Your Practices

Maintain records of:

- What data you collected and when

- The source URLs

- Whether the data was publicly accessible

- Your intended use of the data

- Whether the data was publicly accessible

- The source URLs

Documentation helps demonstrate good faith if questions arise.

Conclusion

The hiQ Labs v.LinkedIn case established that accessing publicly available data generally does not violate the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.This was a significant clarification that removed the threat of federal criminal prosecution from many legitimate scraping activities.

But the case also showed that legal risk extends beyond the CFAA.Terms of service violations, privacy regulations, copyright claims, and state laws all independently constrain data collection.hiQ "won" on the CFAA question but still agreed to pay damages and destroy its data.

The lesson for practitioners: scraping publicly visible data is legally defensible, but it is not a free pass.Respect access controls, understand the terms you are working under, handle personal data carefully, and choose tools that operate transparently within these boundaries.

Ready to extract data the right way ? Install Lection and start collecting publicly available data directly in your browser.

---

Related Reading

- [Web Scraping Legality by Country(2025)](/blogs/web - scraping - legality - by - country - 2025)

- [Complete Guide to robots.txt for Web Scrapers](/blogs/complete - guide - to - robots - txt -for-web - scrapers)

-[Web Scraping Glossary: 50 + Terms Explained](/blogs/web - scraping - glossary - terms - explained) - Explore all tutorials and guides